When I first started writing on Substack, I wrote about an 1987 incident in Zimbabwe, called the New Adam’s Farm Massacre, which can be googled, but I won’t describe here, that transformed me from a kid content to explore the mountains of Idaho to someone whose view of the world changed and darkened as my international experience deepened. I carried two conflicting views: the world was full of goodness and beauty, and the world was a truly awful place where existence is too often brutal and short. What I didn’t understand for most of my life, and have only recently come to understand and embrace is that I can choose which view I use to understand the world.

And that brings me to something wonderful. Before I heard about the New Adam’s Farm massacre, I learned that my wife was pregnant with our first child. I clearly remember having a dream several months before we learned about our pregnancy (and I want to emphasize the “our” part because even though I didn’t do THE heavy lifting, I did a lot of other HEAVY lifting) that left me wistful and filled with longing for a child. I also remember trying to hold onto those feelings in the following days. I couldn’t forget the thought of how it would feel to be a dad. I wanted to hold and hug that child in my dream.

When we returned to Zimbabwe early in 1988, one of our first tasks was to find a doctor, and upon the advice of a trusted Zimbabwean friend, we booked our first prenatal care appointment. The doctor was a kindly older man nearing retirement who, upon seeing the reams of documents and sonogram images we brought from our doctor in Idaho, scanned through them quickly and handed them back. “You Americans and your need to complicate things,” he said gently, and I think he also mentioned something about rubbish. He then pulled a 3”x5” card from a drawer and wrote down the basics such as blood pressure and weight. We paid the receptionist Z$200 (about $100 US) for the prenatal care and delivery fee on our way out.

We also signed up for Lamaze classes taught by a sweet Catholic sister at Bulawayo’s Mater Dei Hospital. I don’t remember how often we drove the 45 kilometers to town or how many classes we attended, but I do remember when the sister described some of the “discomforts” of childbirth. A white Zimbabwean farmer’s wife who was already the mother of several children blurted out from the back of the room. “Discomfort? It hurts like hell, sister!”

Then one Saturday morning, my wife told me that it was time. She was packed and ready to go, and I drove with amazing calm during the one hour trip in a red Peugeot 504 to the hospital in Bulawayo. Later, when I thought about that trip, it never crossed my mind how a few days later, we would return as a family of three. But I had one job that morning. One job.

It was not an easy delivery and there was a shortage of pain medications in the country, but my wife somehow endured the ordeal and about midnight on April 30, she held in her arms a little baby girl. (Someone once told me that the nearest experience to childbirth for a man was passing kidney stones. I mentioned it to a nurse once when I was undergoing treatment for a particularly bad kidney stone that it was like having a baby. She looked me in the eye and said, “And if you thought your wife had anything to do with it, I doubt you would never let her touch again.”)

I was flooded with emotions as I watched my wife with our newborn, but not for long, because the sweet Catholic sister escorted me out of the room so the two could rest. I spent the rest of the night at a friend’s home, unable to sleep as I replayed the day over and over in my mind.

Early Sunday morning, I drove back to our house to collect some things we had forgotten. I was engrossed in my thoughts as I drove through the African bush until suddenly, I heard metal crunching, a dark object blocking my view through the windscreen, more metal crunching, and a fleeting glimpse of a kudu bull crashing through the mopane trees along the road. Somehow the big animal managed to damage both fenders, but nothing else. “TIA,” I thought, “This is Africa!”

Fast forward to a few years ago when I stood with my daughter’s arm holding mine as we walked down the grassy slope to where her groom and wedding party were standing on a little river beach. Just before we started our walk, she decided to take off her shoes so she wouldn’t slip on the grass, and from where I sat during the ceremony, I could see her moving her toes in the sand, as she did as a child when we went to a beach.

I thought about how she once complained to me about wanting to find a guy who was more of a man than she was. “Dad, some of them can’t build a camp fire or even change a flat tire.” The young man she was pledging her love and life to certainly met her basic requirements and much more. It was one of the best days of my life.

Between these two bookends in her life and mine, I experienced much agony and at times, ecstasy, that I never told her about. Much of it was almost too hard for me to think about, and it was out of the question to share those unshared experiences with a child. Yet she somehow always understood me. It must be that special bond between fathers and daughters that I can’t explain, but can only marvel at.

Once, when I was admitted to Johns-Hopkins Hospital because of a recurring skin infection I managed to acquire during one of my trips back to Africa, they drew several vials of blood for screening, including one specially colored vial for a HIV test. I couldn’t sleep because of my near permanent jet lag, so I worried for long hours about why I wasn’t told the results of the HIV test. It didn’t occur to me to just ask.

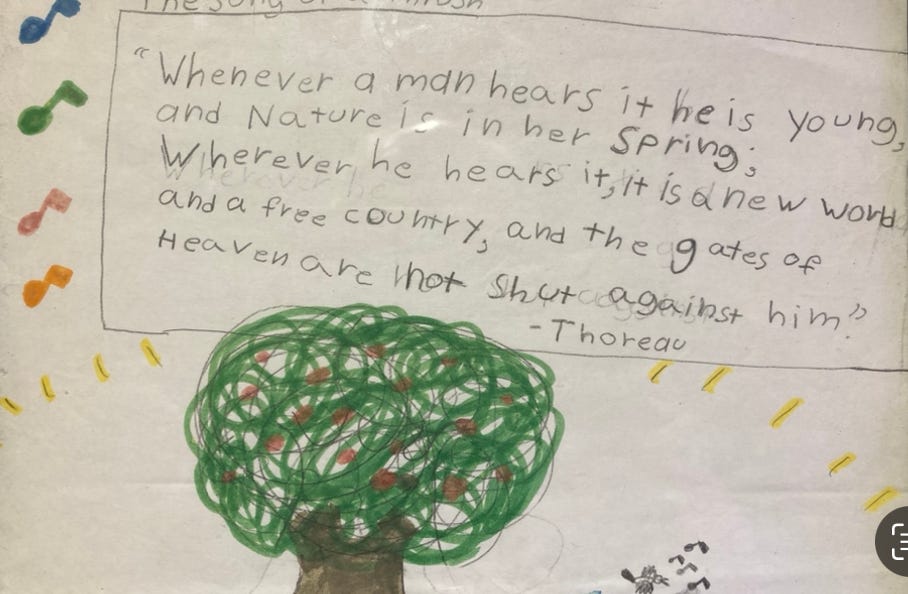

The next evening, as I prepared for another long sleepless night, my family made a surprise visit so my daughter could give me something she made for me that day. On a sheet of copier paper, she used crayons to draw a tree that looked like a cross between an apple tree and a baobab tree. Next to the tree is a little man holding two balloons and a yellow bird flying away surrounded by musical notes. At the top of the page, on a slight angle, she wrote her name and age (9 years old). Between that and the tree, in a big cartoon voice bubble, she wrote something I once read to her.

“Whenever a man hears it, he is young. Whenever he hears it, it is a new world, and a free country, and the gates of Heaven are not shut against him. - Thoreau”.

Somehow she remembered a time when we listened to a thrush together and I read to her what Thoreau had written about the song of a thrush. I slept well that night and ask the nurse the next morning about the test result. “You are fine,”she said after I told her how worried I was. “Why didn’t you just ask?”

On Father’s Day one year, my daughter told me her gift was an entire day she had planned for us to spend together. I met her in Boise for a lunch at one of her favorite places that I knew would be a favorite place for me also because she is our foodie and I trust her judgment about those things. After a wonderful lunch, she took me to a nearby theatre to see “Top Gun - Maverick.” I asked her why she chose Top Gun. “Oh dad, you know I watched the first one with you about ten times, and whenever we went flying in our airplane with our friends who also flew, you guys always were talking about being too close for missiles and switching to guns. I probably know all the Top Gun dialogue.” “But Top Gun is a chick flick,” I said. “Just the right amount of chick flick and guy stuff,” she replied.

A few days after Top Gun, she sent me an email that contained a message that I don’t yet properly understand myself, yet she does:

I am thinking today about the men who grew up without fathers, or with fathers who did harm. Who then attended to their own pain, grief, shame, and rage. Who then become fathers themselves. Who now shine on the next generation with their tenderness, self-awareness, and presence. I am thinking of you because breaking a cycle is an act of heroism. Happy Father's Day. (Dr. Alexandra H. Solomon)

So here are the kinds of worldviews I can choose from: the kind of world I experienced as a child, the kind of world I experienced in my work life, or the better, truer world I experience as a father, a husband, a friend and as someone who is beloved. All require a level of trust and acceptance that they best explain the story of my life, but I have a choice of which one is the world I choose to focus on.

It’s like a bumper sticker I saw on a car not long ago. “I want to be the kind of person my dog thinks I am.”

I want to be the kind of person the people who love me think I am.

Absolutely true and oh so beautiful! Love all the word pictures and experiences shared - can almost imagine many of them! Your lovely daughter has captured and understands her dad’s skill and insight with words and feelings.

Wrecked me. So beautiful. The imagery of your daughter wiggling her toes in the sand like she was a child was just perfect. You’re a great dad man - I’m happy she lets you know.